Building Resilient Health Systems: Equitable Care in a Changing Climate

Building Resilient Health Systems: Equitable Care in a Changing Climate

The climate crisis is no longer a distant environmental worry; it is the definitive global public health challenge of our era. From devastating heatwaves and rising vector-borne diseases to climate-fueled migration and strained infrastructure, the fingerprints of a changing climate are increasingly visible on our hospitals, clinics, and communities.

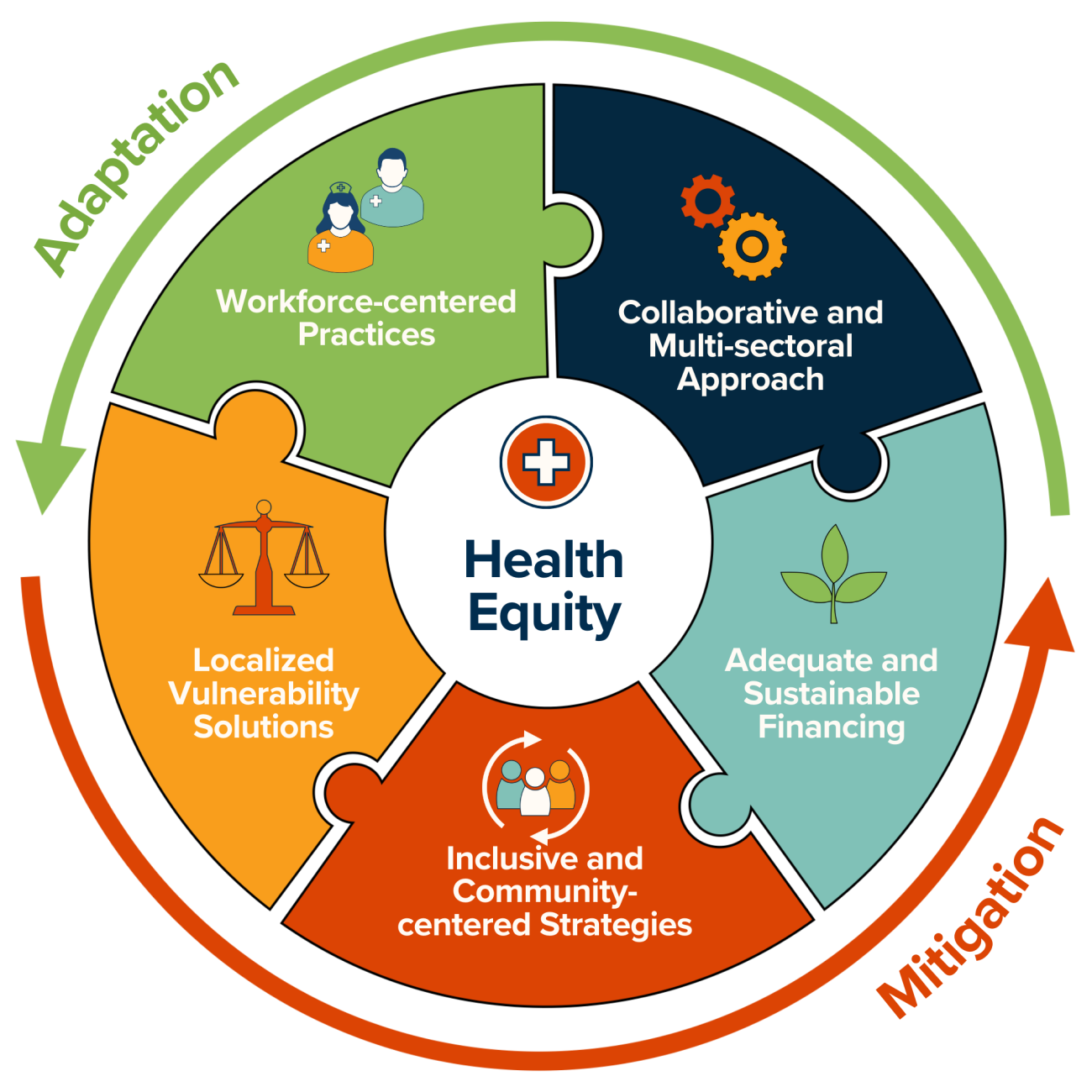

To secure human health in the 21st century, we must move beyond simply ‘reacting’ to climate events. We must actively build truly resilient health systems—systems robust enough to withstand catastrophic shocks while fundamentally committed to delivering equitable care to every population, regardless of geography or socioeconomic status.

The Unstable Nexus: Climate Change as a Health Threat

The resilience of current health systems is defined by their capacity to adapt and recover. Yet, climate change assaults this capacity on multiple fronts:

Infrastructure Failure: Extreme weather events—floods, fires, and superstorms—directly destroy health facilities, disrupt supply chains (medication, oxygen), and cut off crucial access roads. If hospitals cannot operate during a crisis, the system has failed.

Increased Disease Burden: Rising global temperatures expand the range and season of vectors like mosquitoes and ticks, accelerating the spread of diseases such as dengue, malaria, and Lyme disease. Health systems must simultaneously handle environmental crises while managing complex epidemics.

Workforce Strain: Climate-related disasters place immense pressure on healthcare providers, leading to burnout, staff relocation, and an inability to deliver consistent primary care, especially in vulnerable regions.

Why Resilience Must Be Built on Equity

While climate impacts are universal, they are not experienced equally. The populations that contribute the least to global warming—low-income communities, Indigenous populations, the elderly, and those living in climate-vulnerable geographies—are often the first and hardest hit.

For these groups, climate hazards intersect with pre-existing social determinants of health: higher rates of chronic illness, inadequate housing (lacking cooling or stable foundations), and limited access to nutritious food and clean water.

In this context, building resilience is inseparable from achieving equity:

A resilient system prioritizes proactive cooling centers for urban residents who cannot afford air conditioning.

A resilient system ensures emergency power backup and medication delivery routes remain open in remote or marginalized neighborhoods often overlooked during recovery efforts.

A resilient system addresses the mental health burden of displacement and loss caused by climate disasters, offering culturally competent support.

If a health system merely recovers its functioning without addressing the disproportionate vulnerability of its weakest links, it is fundamentally unstable and destined for failure during the next shock.

Three Pillars for Building Climate-Smart, Equitable Systems

Moving from recognition to action requires a strategic and targeted approach focused on adaptation, mitigation, and robust governance.

1. Climate-Smart Infrastructure and Mitigation

Health systems must stop contributing to the very crisis they are designed to treat. Globally, the healthcare sector is a significant contributor to carbon emissions. Decarbonization and adaptation infrastructure are twin necessities:

Green Hospitals: Investing in solar microgrids, geothermal energy, and energy-efficient building standards allows facilities to remain operational during grid failures caused by extreme weather.

Water and Waste Management: Implementing sustainable water conservation and resilient medical waste protocols to prevent contamination and conserve resources during droughts or floods.

Supply Chain Localization: Reducing reliance on distant, carbon-intensive supply chains by prioritizing locally sourced medications, supplies, and food, simultaneously strengthening local economies and reducing transport risk.

2. Workforce Preparedness and Mobility

The health workforce is the heartbeat of the system. Preparing them for climate-related threats is paramount:

Climate & Health Curriculum: Integrating climate science, extreme weather response protocols, and environmental justice into medical, nursing, and public health education.

Targeted Training: Training frontline community health workers and primary care providers in identifying and treating heat stress, air pollution exposure, and emerging infectious diseases.

Staff Protection: Ensuring access to disaster hazard pay, mental health support, and stable housing for healthcare workers allows them to reliably serve their communities during and after crises.

3. Data-Driven Surveillance and Adaptive Governance

Effective resilience requires predictive capacity, not just reactive measures.

Early Warning Systems (EWS): Utilizing meteorological data and public health surveillance to anticipate climate-related health risks (e.g., predicting the spread of dengue based on rainfall and temperature) allows resources and interventions to be mobilized before crises peak.

Equity-Focused Metrics: Health systems must track disaggregated data to understand which specific sub-populations are most impacted by climate events. Governance must prioritize resource allocation based on vulnerability maps, ensuring that interventions are targeted to those most in need, rather than merely where infrastructure is easiest to deploy.

Community Integration: Health authorities must establish formal partnerships with community leaders and local civic organizations. These groups often hold critical local knowledge and are essential for reaching marginalized individuals who traditional services may overlook during an emergency.

The Cost of Inaction is Unbearable

Building resilient, climate-smart health systems is a significant undertaking, requiring substantial financial and political investment. However, the cost of inaction—measured in lives lost, perpetual disaster relief, and staggering economic damages—far outweighs the cost of proactive adaptation and mitigation.

Resilience is not a luxury; it is a fundamental requirement for securing global health. By placing equity at the heart of our climate adaptation strategies, we ensure that the systems designed to protect us are strong enough to protect everyone when the next storm arrives.

The fight for climate justice is inherently a fight for health justice. It is time for global leadership and local action to fortify our health systems, ensuring they are not just surviving the climate crisis, but thriving in the service of all humanity.

Post a Comment for "Building Resilient Health Systems: Equitable Care in a Changing Climate"

Post a Comment